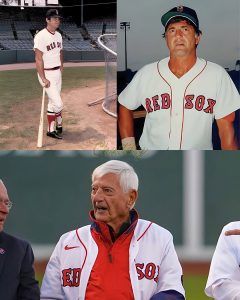

Carl Yastrzemski’s career didn’t begin with cheers. It began with expectations — suffocating ones. When the 21-year-old from Long Island first pulled on a Red Sox uniform in 1961, he was stepping directly into the shadow of Ted Williams, arguably the greatest hitter who ever lived. In Boston, replacing a legend isn’t a job; it’s a burden. And in those early years, every step Yastrzemski took toward home plate felt like a test the city wasn’t sure he could pass.

But he did more than pass. He redefined the entire exam.

Yastrzemski was never Williams — and that may have been the miracle. While Williams dazzled with jaw-dropping dominance, Yastrzemski built his legacy with something quieter and perhaps even harder: mastery through discipline. He studied Fenway’s Green Monster like a scientist, breaking down angles and bounces until left field became his personal kingdom. Seven Gold Gloves would eventually follow. So would a reputation as one of baseball’s most intelligent defenders — a man who turned ricochet reads into an art form.

Still, the offense took time. His first two seasons were solid, not spectacular. The pressure lingered. The comparisons never stopped. And then came 1963 — the year everything changed. Yastrzemski hit .321, led the league in doubles and walks, and finally stepped out of Williams’ silhouette. Boston fans began to understand: this wasn’t “the next Ted Williams.” This was the first Carl Yastrzemski.

Four years later, in 1967, he authored one of the greatest individual seasons in baseball history. The Triple Crown. A .326 average, 44 home runs, 121 RBIs. A September that felt mythical — seven hits in eight at-bats over the final weekend, carrying a franchise that hadn’t touched a pennant in more than two decades. Every swing felt like defiance, as if he were willing Boston back to life.

The Red Sox came up short in the World Series, unable to solve Bob Gibson. But even then, Yastrzemski hit .400 with three homers, leaving the season as MVP, Sportsman of the Year, and the beating heart of a team reborn.

His prime years were a tapestry of brilliance and brutality — a batting title in 1968 with the lowest average ever to lead the league, a .329 season in 1970 where he fell short of the crown by less than a thousandth, 40-homer campaigns in ’69 and ’70, an All-Star Game MVP, and postseason performances that often elevated him above the numbers on the page.

There were heartbreaks too. The Game 7 loss in 1975. The Bucky Dent game in 1978, where he made the final out. But even that afternoon, he managed something extraordinary: homering off Ron Guidry during the finest pitching season of Guidry’s career — the only lefty to do so.

That was Yastrzemski. He didn’t promise perfection. He promised presence.

In a city that worships loyalty and work ethic as much as trophies, Yastrzemski became more than a player. He became an anchor. A constant. The kind of figure whose legacy grows not only through triumphs but through the simple, stubborn refusal to fade.

He began as “the man after Ted Williams.”

He finished as a legend all his own.

Leave a Reply