Uncovering the Talpiot Tomb: The Archaeological Mystery of Jesus and His Family

The death of Jesus of Nazareth, over two millennia ago in first-century Jerusalem, remains one of history’s most significant events.

According to the Gospels, he was crucified by the Romans, buried in a tomb, and, within days, the tomb was discovered empty by Mary Magdalene, one of his closest followers.

Yet, the Gospel of Matthew suggests that an alternative story circulated: some claimed that Jesus’ disciples secretly removed his body, perhaps to provide a proper family burial.

If this were true, it would align with Jewish burial customs of the time, where bodies were laid in rock-cut family tombs, left to decompose, and later placed in ossuaries, or limestone coffins, for final interment.

For centuries, the resting place of Jesus remained a matter of theological belief and historical speculation.

That changed in 1980, when construction work in South Jerusalem unearthed an ancient tomb, later named the Talpiot Tomb.

The excavation revealed a rock-cut tomb containing ten ossuaries, six of which bore inscriptions of names that would later astonish scholars and ignite debates: Yeshua son of Joseph, Maria, Yose, Matia, and others corresponding to members of Jesus’ family according to Gospel accounts.

The discovery immediately raised questions.

Was this the family tomb of Jesus?

Was it merely a coincidence that these common names appeared together, or did it point to a groundbreaking historical revelation?

Archaeologists and statisticians would later attempt to answer these questions through a combination of on-site investigation, textual analysis, and forensic science.

The Talpiot Tomb itself was an intricate structure, with a central chamber, arcosolia benches carved into the walls, and deep cavities or loculi designed to house multiple ossuaries.

Among the inscriptions, “Yeshua bar Yosef” — Jesus son of Joseph — stood out.

Although the name itself was not uncommon at the time, its association with other names found in the tomb, including Maria, possibly representing the Virgin Mary, and Yose, a diminutive of Joseph consistent with Jesus’ brother mentioned in the Gospel of Mark, suggested a familial cluster.

Further inscriptions provided additional layers of complexity.

One ossuary bore the name Mariamne, a rare variation of Mary, while others held names such as Matia, aligning with known relatives from Gospel genealogies.

The presence of these names in a single tomb was statistically significant.

Professor André Royo-Burger, a leading mathematician and statistician, conducted an analysis of first-century Jerusalem names and concluded that the probability of such a combination occurring randomly in a tomb was exceedingly low, suggesting that this could indeed be the tomb of Jesus’ immediate family.

![Bên Lòng Chúa] Yêu và được yêu... CN VI PS - YouTube](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/Su0o_yrEe64/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwEhCK4FEIIDSFryq4qpAxMIARUAAAAAGAElAADIQj0AgKJD&rs=AOn4CLAHMDDvAzqpKk_joYrGMk4bd5_RiA)

Despite the potential significance, the Talpiot Tomb remained largely unnoticed for decades.

Archaeological authorities cataloged the ossuaries and reburied the remains following the requests of the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community.

This cautious approach delayed public awareness and scientific inquiry, leaving the tomb’s significance largely dormant.

Yet, modern techniques, including forensic DNA analysis, began to shed new light on these ancient relics.

One of the most compelling findings came from the Mariamne ossuary, which some scholars speculated could belong to Mary Magdalene.

Known historically as a close and influential follower of Jesus, Mary Magdalene’s presence in such a tomb would challenge long-standing assumptions about her role and potentially indicate a marital connection with Jesus.

Forensic studies focused on mitochondrial DNA from the ossuaries, aiming to determine familial relationships.

The tests revealed that the DNA from Yeshua bar Yosef and Mariamne did not indicate a maternal relationship, suggesting they were not siblings, but possibly husband and wife, further deepening speculation about Mary Magdalene’s role in Jesus’ life.

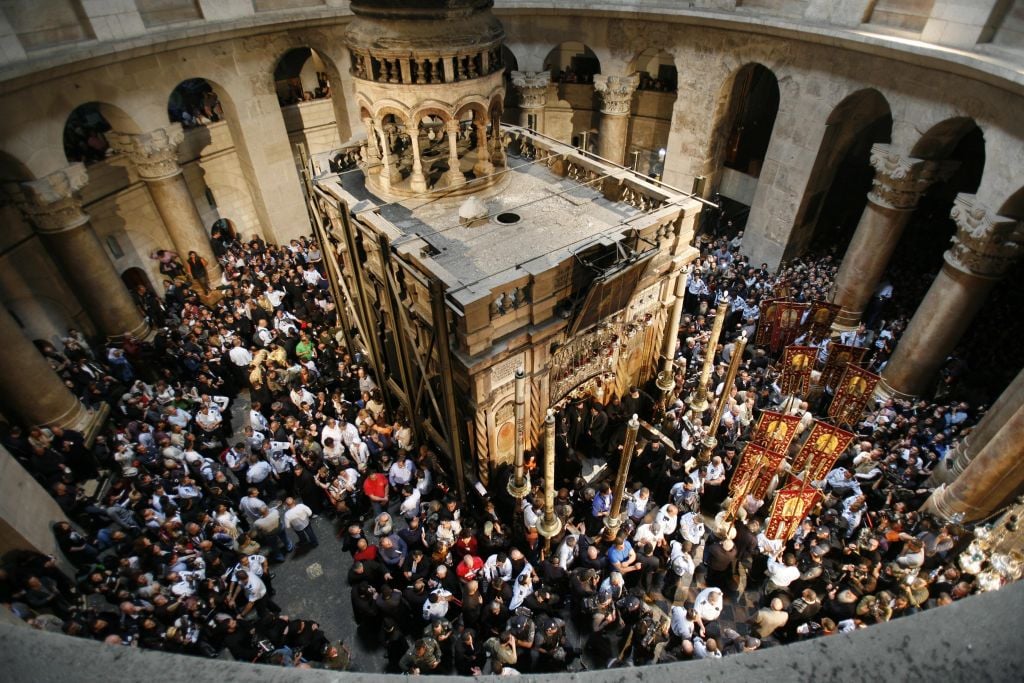

The Talpiot Tomb discovery is not the only archaeological site linked to the early followers of Jesus.

Excavations at Dominus Flevit, a site overlooking the Temple Mount, revealed a cemetery containing ossuaries inscribed with names of prominent early Christians, including Simon bar Jona (Peter) and Simon of Cyrene, known from the Gospels as the man who helped Jesus carry the cross.

These finds establish a broader context for early Judeo-Christian burial practices in Jerusalem, demonstrating that followers of Jesus were buried in identifiable tombs and may have maintained close familial or communal burial sites.

The Talpiot Tomb inscriptions also featured symbols, such as a circle with a cross-like design, which some scholars suggest could represent early Christian iconography, predating the widespread use of the cross as a symbol of faith.

These symbols hint at the existence of a vibrant, clandestine early Christian movement within Jewish society, one that may have disappeared from historical prominence after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE but left tangible traces in the form of ossuaries and tombs.

Further complicating the narrative is the disappearance of one of the Talpiot ossuaries.

Records indicate that of the ten originally cataloged ossuaries, one has gone missing, only to reappear decades later in a private collection.

Inscribed as “James son of Joseph, brother of Jesus,” this ossuary has renewed debates over the historical reality of Jesus’ siblings and their role in the early Christian movement.

James, according to early Christian tradition, became a prominent leader of the Jerusalem church, guiding followers and preserving the teachings of his brother.

Historians and biblical scholars remain divided on the implications of the Talpiot Tomb.

Skeptics argue that the names inscribed on the ossuaries were common during the first century, cautioning against drawing direct historical connections.

However, proponents highlight the statistical rarity of the specific combination of names and familial relationships, suggesting that the tomb could indeed represent the family of Jesus.

In particular, the unique forms of names, such as Mariamne and Yosa, align closely with Gospel references, strengthening the argument for a direct link.

Beyond the historical and archaeological questions, the Talpiot Tomb invites a reevaluation of early Christian narratives.

If Jesus and Mary Magdalene were indeed buried in this tomb, it challenges traditional interpretations of their relationship, the role of women in the early movement, and the timeline of Christian traditions that emerged centuries later.

Texts such as the Acts of Philip and the Gospel of Mary Magdalene, rediscovered in the 20th century, depict Mary Magdalene as a respected apostle, teacher, and missionary, offering a historical basis for her presence in a family tomb alongside Jesus.

The Talpiot discovery also emphasizes the interplay between archaeology, faith, and scholarship.

While the presence of physical remains could reshape historical understanding, it does not necessarily undermine Christian faith.

Many theologians argue that spiritual significance, resurrection, and ascension are matters of faith, independent of the physical location of Jesus’ remains.

Nevertheless, the tomb provides an extraordinary opportunity to study early Jewish-Christian practices, burial customs, and familial networks that have long been obscured by centuries of religious interpretation.

Modern technology, including remote cameras, ground-penetrating surveys, and ancient DNA analysis, continues to offer new insights.

Efforts to locate the precise tomb beneath modern apartment complexes in Jerusalem illustrate the challenges of urban archaeology, where historical sites often lie beneath contemporary infrastructure.

The meticulous documentation and analysis of ossuary inscriptions, decorative motifs, and burial layouts allow scholars to reconstruct social, religious, and familial patterns of the time.

The Talpiot Tomb, along with associated finds at Dominus Flevit and other Judeo-Christian cemeteries, paints a picture of a historically grounded movement of early followers of Jesus.

These sites suggest a cohesive community maintaining familial and religious traditions, buried in identifiable tombs with inscriptions, symbols, and ossuaries reflecting both cultural norms and spiritual devotion.

DNA evidence and statistical analyses provide tantalizing hints of relationships within these tombs, opening discussions about the potential marriage of Jesus and Mary Magdalene, the roles of his siblings, and the broader structure of the early Jesus movement.

Ultimately, the Talpiot Tomb discovery challenges scholars and the public to reconsider the boundary between history and faith.

It reveals a rich archaeological record that aligns with Gospel narratives, yet remains open to interpretation.

Whether the ossuaries contain the actual remains of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and their family, or represent a remarkable coincidence, the site underscores the enduring fascination with the historical figure of Jesus and the world he inhabited.

As archaeological methods advance and more evidence emerges, the Talpiot Tomb offers a rare window into first-century Jerusalem, its burial practices, and the intimate networks surrounding one of history’s most influential figures.

While many questions remain unanswered, the intersection of names, inscriptions, symbols, and DNA evidence ensures that the tomb will continue to captivate historians, archaeologists, and the faithful alike.

It stands as a testament to the enduring legacy of Jesus, Mary Magdalene, and their early followers, whose lives, beliefs, and resting places continue to spark discovery, debate, and wonder.

Leave a Reply