A discovery so unsettling that it is quietly rattling both laboratories and churches has thrust the Shroud of Turin back into the center of global debate. Long dismissed by skeptics as an ingenious medieval fake, the ancient linen is now at the heart of new research that suggests something far more explosive: the shroud may indeed be the burial cloth of Jesus Christ—and its image may record an event science cannot yet explain.

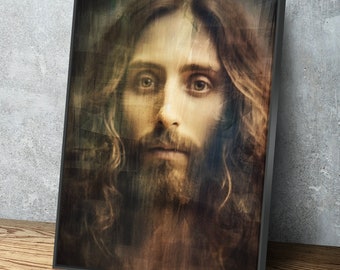

For over 700 years, the Shroud of Turin has divided the world. A 14-foot linen cloth bearing the faint front-and-back image of a crucified man, it has been analyzed for more than half a million research hours by physicists, chemists, doctors, and historians. Yet no paint, dye, pigment, or known artistic technique has ever been found. The image exists only on the outermost fibers—so shallow that scraping the cloth destroys it entirely. It is not burned, not drawn, and not woven in.

What has reignited the controversy is a radical new interpretation of how the image could have formed. According to recent experimental models, the discoloration may have been caused by an instantaneous burst of radiant energy—so intense that it would have required the equivalent of 34 trillion watts, released in a fraction of a second. No known natural process can generate such energy. No medieval technology could even approach it. And most disturbingly, the energy appears to have come from within the body wrapped by the cloth.

Even more troubling for skeptics is the blood.

Chemical analysis has revealed unusually high concentrations of creatine and ferritin in the stains—biomarkers associated with extreme physical trauma, massive tissue breakdown, and violent death. These are details modern forensic medicine only fully understood in the 20th century. How could a medieval forger anticipate biochemical signatures that science itself would not identify for another 600 years?

The case grows darker when the shroud is compared to the Sudarium of Oviedo, a separate cloth believed to have covered Jesus’ face. The Sudarium has a documented history reaching back to the 6th century—centuries earlier than the shroud’s first known appearance in Europe. Yet when forensic teams overlaid blood patterns from both cloths, the wounds aligned with eerie precision: the same nose injury, the same head trauma, the same blood flow angles. Two cloths. Same body. Same moment in time.

Then came the linen itself.

Advanced molecular studies now suggest the fiber structure matches burial cloths used in first-century Judea, not medieval France. This has cast serious doubt on the famous 1988 carbon dating, which placed the shroud in the Middle Ages. New analysis indicates the tested samples may have come from a repaired section—added after a fire in the 1500s—meaning the dating may have been catastrophically flawed.

Pollen analysis only deepens the mystery. Dozens of pollen grains embedded in the fibers match plant species native to Jerusalem and surrounding regions—plants that do not grow in Europe. Some of these species went extinct centuries ago. Their presence suggests the cloth once traveled through the very landscapes described in the Gospels.

And then there is the image itself.

Up close, it is nearly invisible. Step back—and a face emerges. Even more astonishing, the image behaves like a photographic negative, a property not discovered until the invention of photography in the 19th century. No medieval artist could have conceived such an effect, let alone executed it accidentally.

Skeptics warn against sensationalism. But even among critics, the language has changed. The shroud is no longer dismissed as a simple forgery. Instead, it is increasingly described as an “unsolved phenomenon.”

For believers, the implications are staggering. If the shroud truly wrapped Jesus of Nazareth, then the image may not depict death—but the moment after death. Not decay. Not burial. But transformation.

Leave a Reply